Gender Experiences and Representations in Facism

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Arts |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3455 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Analyse the ways in which gender was thought about, experienced and represented under Fascism.

Fascism is defined by Victoria De Grazia as ‘culture of consent’[1] because all levels of society were monitored and controlled. Mussolini regulated every aspect of people’s lives, including gender and identity of Italians. Teresa de Lauretis has remarked that gender in any given period is a cultural construction rather than a simple derivative of biological difference[2], and as a cultural construction in this paper it will be shown how it reflects the Italian misogynistic society of that time. In this essay, this construction will be presented and it shall demonstrate that gender during Fascism was thought, represented and built in manners which would have supported Mussolini’s goals, the regime’s interests and the creation of the empire. Firstly, the Fascist idea of gender roles will be introduced and its usefulness will be analysed. Next, it will be shown that, like other elements of the dictatorship, this concept of gender was contradictory. Further, the impact that these new norms of gender identity had on people’s lives will be examined. Finally, will be analysed how gender was represented. Before understanding why a certain image of ‘new man and woman’ was needed and created under the regime, it is necessary to understand how sexuality was considered.

In Fascist virilities Spackman argues that Marinetti’s view strongly influenced how gender was thought about. In Contro il matrimonio Marinetti wrote: ‘La donna non appartiene a un uomo, ma bensì all’avvenire e allo sviluppo della razza’ and ‘Sara’ finalmente abolita la mescolanza di maschi e femmine che nella prima eta’ produce una dannosa effemminazione dei maschi.’[3] The poet argues that marriage and family are threats to virility. Moreover, in the Manifesto del futurismo he glorifies militarism, war, patriotism, scorn for women and the destruction of feminism.[4] Fascism, influenced by this idea, claimed that women and men were different by nature and their education and development should have been different. They also underlined that, for biological reasons, men were superior to women. Still, as Willson shows in Peasant women and politics in Fascist Italy, others argue that there was an equality of the sexes since no individual of either sex had rights. Instead, both sexes had obligations to the state.[5]

There were different roles that women and men had in Fascist Italy, being useful to the regime, some were strongly encouraged through campaigns and propaganda, while others were tackled. The ideal Fascist woman was the donna madre, who was considered the ‘new woman’, but represented a shift back to a traditional ideal about females. She must obey, take care of the house, serve her family’s needs, yet at the same time serve the state. Her main job is to produce children. Motherhood is the only element that defines her, she is the mother of the nation who would fulfil Mussolini’s pronatalist policies. The donna madre is depicted as traditional, patriotic and rural. The model of massaie rurali was especially exalted, and propaganda extolled them as the most praiseworthy of Italian women since they were the most prolific. Secondly, there is the donna tipo 3, she worked all day in the office, didn’t respect her husband and was reluctant about maternity. Thirdly, the worst was the donna-crisi, she was thin, hysterical and sterile. Contrarily, masculine identity was virile, strong, heroic and dominant in society and family as we can see that from the words of the magistrate Giuseppe Maggiore: ‘Il Fascismo e’ maschio. Il Fascismo e’ suscitatore di virilità contro ogni infemminimento e infrollimento dello spirito.’[6] During these twenty years, great importance was given to virility, especially through the exaltation of militarism. We must remember that Fascism developed between the two world wars. Thus, the ideal ‘new men’ were the Roman soldier and the rural man, in his natural and untamed masculinity. Instead, the modern, bourgeois civilization would have caused the decay of virility, as well as the intellectual, who was passive and fragile.

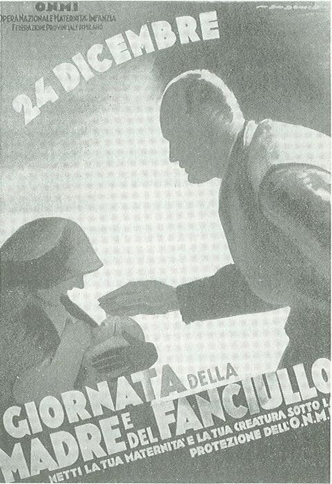

How are these gender roles connected to Mussolini’s plan? As De Grazia claims in How fascism ruled women: ‘Every aspect of being female was thus led up to the measure of the state’s interest and interpreted in light of the dictatorship’s strategies of state building.’[7] Firstly, the new woman had to be inferior in order to fix the crises of masculine identity, caused by the humiliating defeat of Caporetto. Her image is created in order to confirm male superiority. Secondly, in order to build his empire, Mussolini needed more people, specifically, more soldiers, otherwise Italy would have been unable to stand up the other European powers. This is clear in his discorso dell’ascensione, a speech given on May 26th 1927. The Duce said: ‘cosa sono 40 milioni d’Italiani di fronte a 90 milioni di Tedeschi e a 200 milioni di Slavi? Signori, l’Italia, per contare qualche cosa, deve affacciarsi sulla soglia della seconda metà di questo secolo con una popolazione non inferiore ai 60 milioni di abitanti.’ and ‘Se si diminuisce, […] non si fa l’impero, si diventa una colonia’.[8] The falling birth rate was considered ‘the problem of problems’ and was portrayed as a national emergency. His goal was to increase the population to 60 million. This is the origin of the ‘Battle for births’ and unprecedented official attention to women, which now were considered important for the country and had the opportunity to serve it with childbearing. This is how the image of the donna madre was originated. The proof of that are the numerous pro-natalist and pro-marital measures such as the ‘bachelor tax’, prizes and benefits for prolific mothers and repressive measures against fertility control. Moreover, from 1933 a ‘Mother and a Child Day’ was celebrated and prolific mothers were publicly honoured for the numbers of their offspring. The other reason why the role of mother was exalted is that a growing population provided Mussolini with a reason for demanding colonies and supplied the military manpower needed to conquer them, in fact, an article in Il Popolo d’Italia stated ‘we need soldiers rather than philosophers’[9]. To conclude, it will be clarified how the characteristic of ‘queen of the home’ of the ideal Fascist woman/mother was created. The origin of that is the economic crisis, which developed after the first world war. While men went to war women took their jobs. After the war, men wanted it back and the result of that is the gender struggle, as Graziosi says. Men claimed that women’s employment was causing men’s unemployment and commanded them to go home, where they really belonged.[10] Women had to stop working and this was obtained through the legge Sacchi. They were excluded from the labour force and segregated in a few non-existent vocational jobs, such as segretaria sociale and assistente sanitaria. These measures and reforms show the connection between the construction of gender and the regime’s interests.

Their assertion fails when we underline some of the regime’s contradictions. Women were first prevented from working, because it caused the crisis and the low birth rates, as Pickering-Iazzi underlines: ‘Only men involved in economic production are figured as capable of sexual reproduction, whereas involvement in economic production is presumed to destroy the women’s ability to reproduce.’[11] In order to validate that in 1934 Mussolini outlined the dangerous effects that work had on women: it causes physical issues, estrangement from home and family life. Nevertheless, in 1939 they will be called to substitute men who left for the war.

In the next paragraphs, the impact that Fascism had on people’s lives will be analysed, focusing on women. Pickering-Iazzi said ‘the regime constructed new apparatuses in the forms of policies, programs, and institutions designed to cultivate and manage a patriarchal agenda for female culture.’[12] In this essay we are investigating that gender was built in a way that would have helped the regime to reach its goals, in fact, to pursue its population politics, Fascism sought to establish control over female bodies, especially reproductive functions. This started in 1926 with the Italian low birthrate and the pro-natalist campaign that led to many reforms that restricted women to the reproductive function, resulting in estrangement from the public sphere. The state criminalised abortion, banned the sale of contraceptive devices and sex education, supported by the Church. Women were uninformed and they blindly accepted their condition of mothers. Moreover, the regime created birth bonuses, maternity insurance and established the national agency Opera Nazionale per la Maternita’ e Infanzia to oversee maternal and infant welfare. On 1933 they created the annual ‘Mother and Child Day’ to honour prolific mothers, presented as the best sample of the race. Regarding men, they only instituted a tax on bachelors. The dictatorship’s misogyny was manifest in its policies toward schooling young women and the employment legislation. It excluded and discriminated them since work was considered contrary to the female physiology, dangerous for reproduction and risky because it reinforced women’s independence. They weren’t allowed to become headmistresses, they were banned from teaching most prestigious subjects and excluded from the private sector.[13] Once in school, they were educated as wives and mothers, learning childcare techniques and domestic science. Afterwards, girls were discouraged to undertake higher studies, with discriminatory fees from which boys were exempted. These amendments confirm that Gentile’s reform was openly sexist.

To exploit women’s desire for social engagement they established new kinds of gender-segregated youth organisations. From 6 years old girls were under the Fascist control, enrolled in piccole/giovani italiane and giovani Fasciste. The socio-cultural practices led by mass organisations endorsed the patriarchal values that the Fascist state represented in order to build their idea of gender identity. Girls were convinced that their only mission was maternity and were trained in feminine jobs such as childcare, cooking and gardening. Their treatment was unequal to that of the boys, who did competitive sports and paramilitary activities to fight femininity and form the masculine identity that would have furnished the future soldiers of the 3rd Rome. Italians’ leisure time was also supervised by the regime, through Dopolavoro circles where they were harassed with propaganda. Women were excluded from many centres of social life, like bars and cafes and forced to turn to mass leisure activities, that reinforced the vision of the traditional woman. The female version of Dopolavoro was the section of Massaie rurali, rural women promoted as essential players in the empire building. They organised propagandistic events such as rallies, trips to Predappio and LUCE’s documentaries projections that gave women the illusion of escapism from home into the public sphere.[14]

If the regime was so misogynistic, why women like Majer Rizzioli and Labriola supported it? In How fascism ruled women De Grazia suggests that the fact that the regime gave importance to women and defined their rights and duties might be interpreted as a signal of progress, but Gentile’s and the pro-natalist campaign’s reforms confirm Fascism’s anti-modernism. Nevertheless, many women joined the Fasci Femminili and loyally supported the party. It is argued that Mussolini actually ‘supported’ women and their right to vote, as he declared in discorso al congresso dell’alleanza internazionale pro-suffraggio femminile of 1923: ‘io penso che la concessione del voto alle donne avra’ delle conseguenze benefiche, perche’ la donna portera’ nell’esercizio di questi nuovi diritti le sue qualita’ fondamentali di misura, di equilibrio e saggezza.’[15] These women aimed for more presence in the Italian’s political scene and were blinded by Mussolini’s promises, the public recognition and prizes that they were given to balance out. Afterwards, the regime showed its real intentions and the proof of that are the many sexist reforms.

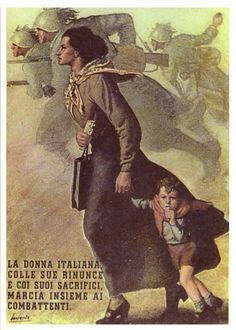

One of the weapons used by the regime, in order that its totalitarian project would penetrate in all levels of society, was the constant propaganda. They tried to define canons of female beauty and masculine identity, in order to fulfil Mussolini’s purpose of an empire full of soldiers and submissive fertile women. They did that especially by glorifying virtues of the rural lifestyle, as Bellassai points out in The masculine mystique: ‘the normative representation of masculinity and femininity were essential ingredients of the rhetorical effectiveness of the antimodernist message.’[16] Propaganda material included calendars, newspapers and films. At the same time, women’s magazines introduced an image of femininity opposite to the Fascist one.

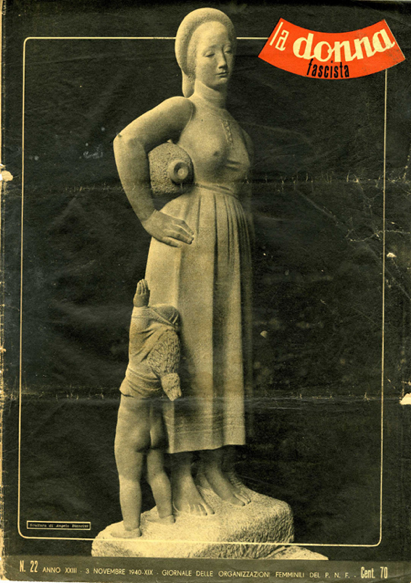

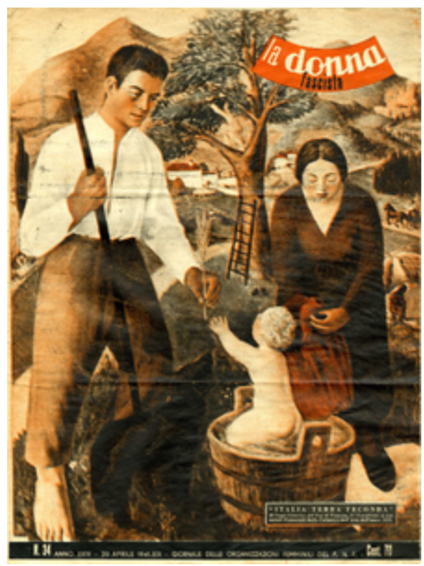

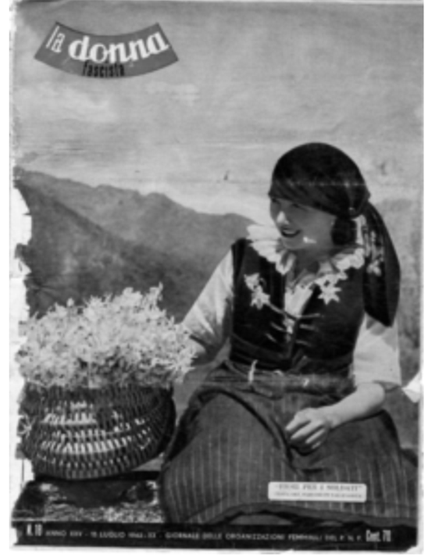

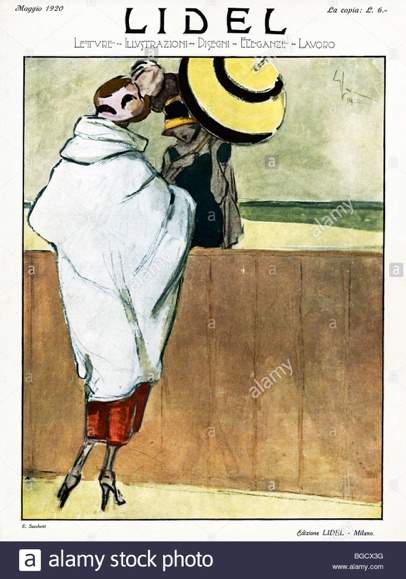

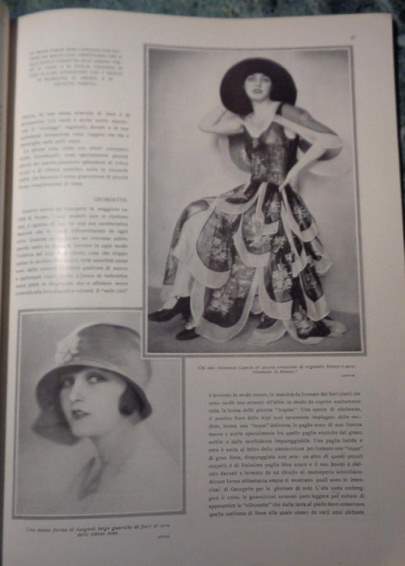

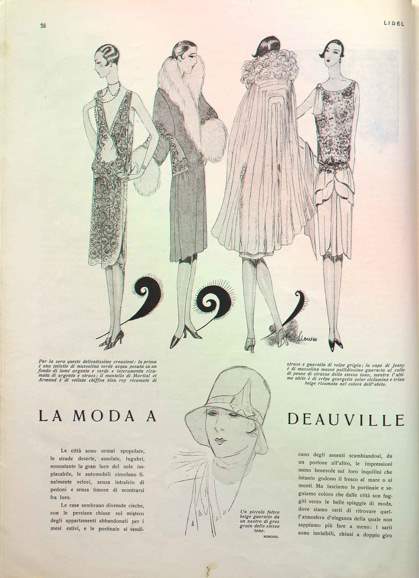

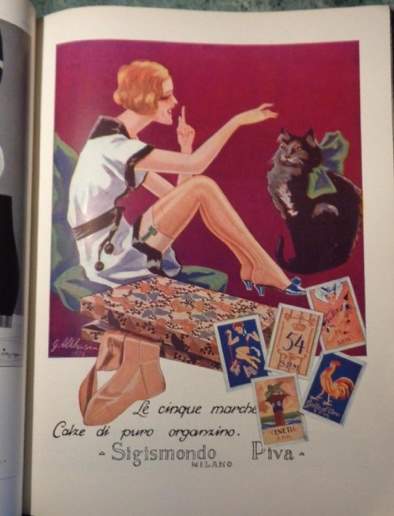

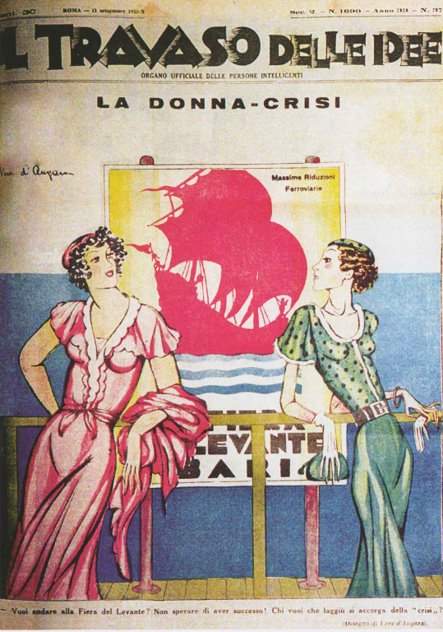

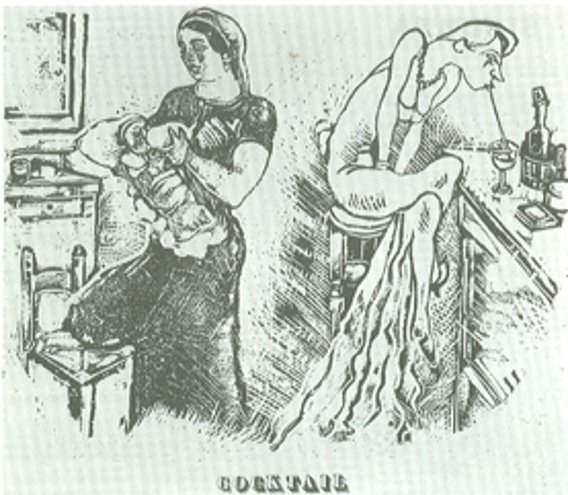

In order to suppress the new awareness of the feminine body and to control the desire of emancipation, the Fascist government produced its own models of bellezza muliebre, and women would become confined by their biology. The ‘authentic’ Italian woman had large breast and wide hips, was traditional, prolific and patriotic: she looked like maternity incarnate. Only in this way she would have been a good companion, able to take care of the house and family. With the help of some pictures, the ideal woman that Fascist propaganda tried to inculcate during the Ventennio will be analysed. Magazines were the most diffused form of propaganda. La donna fascista was a weekly magazine of social female education, managed by the female organisations of PNF. As can be seen from the covers from pictures 1-3, propaganda glorified the virtues of rural life and peasant women were often represented. They were surrounded by children, solid and robust in stature and old in appearance. They were not feminine at all, but femininity was confined at the level of cultural practice. For them, real femininity was in the ability to reproduce. It is always represented a desexualised image that shows a woman who lacks the time to take care of her appearance. The magazines also contained many illustrations and photographs: massaie at a political event, competition prize winners and prolific mothers. Meanwhile, in Italy the riviste femminili like Grazia and Lidel were created, and they advertised a completely different canon of femininity since they were not controlled by the regime. For instance, in the next group of pictures can be seen a woman that shows great modernity, she doesn’t wear rural clothes but she is elegant, sensual, feminine, independent and doesn’t need either a man or a child. These models were imported from America and appealed the feminine public.

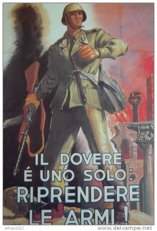

Another means of propaganda were posters, the majority of them were created by ONMI. They all represent mothers, often in rural clothes, surrounded by children. It’s important to underline the fact that they are faceless and the figure is stylised because also in the representation we can see that importance is not given to their identity, but only to their function of bearers of children. Through the last poster, we understand that propaganda boasted the idea that motherhood was a service to the nation and presented it as a privilege. Moreover, the only identity allowed to women, massaia and mother, was also trumpeted through LUCE’s cinegiornali and documentaries in which the right behaviour of Fascist women was shown. ( https://patrimonio.archivioluce.com/luce-web/detail/IL5000023009/2/massaie-rurali-nella-casa-del-fascio-incontrano-maria-jose.html?startPage=0 https://patrimonio.archivioluce.com/luce-web/detail/IL5000025566/2/donne-tutta-italia-acclamano-duce.html?startPage=0 https://patrimonio.archivioluce.com/luce-web/detail/IL3000052373/1/scuole-pratiche-economia-domestica.html?startPage=0)[17]

At the same time, the government fought against the female counterpart of the bourgeois male, which was the donna-crisi. Her caricature was designed to symbolize the dangerous effects of modernization and the sense of independence instilled in Italy’s female population. She was depicted as masculine, thin and sterile. (pic. 6) Since this kind of woman was counter-productive for the regime’s interests, Mussolini launched an anti-slimming campaign and ordered the press to eliminate ‘sketches of excessively thin and masculine female figures who represent sterile female types.’[18] Showing this kind of images women would have aimed to turn into the donna madre and the regime would have eliminated the risk of female emancipation.

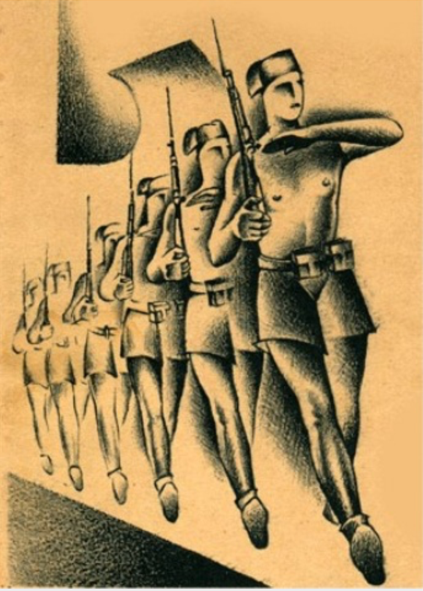

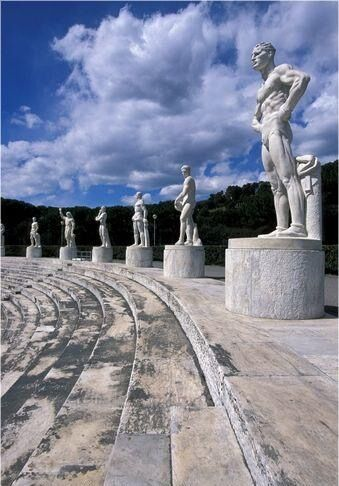

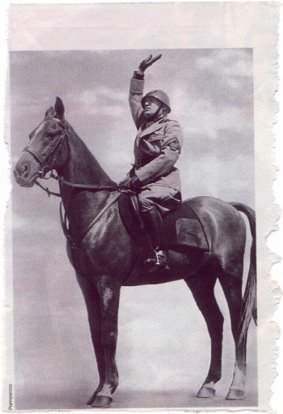

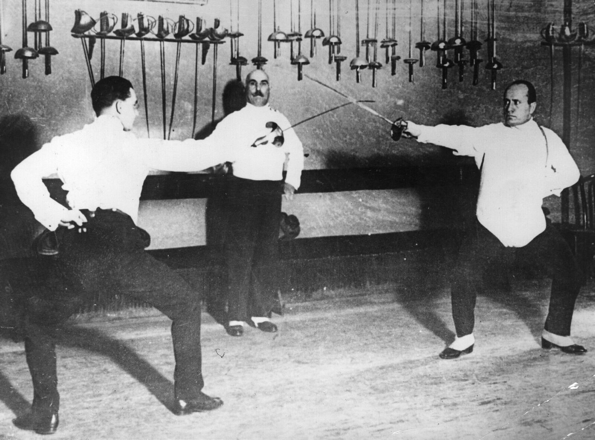

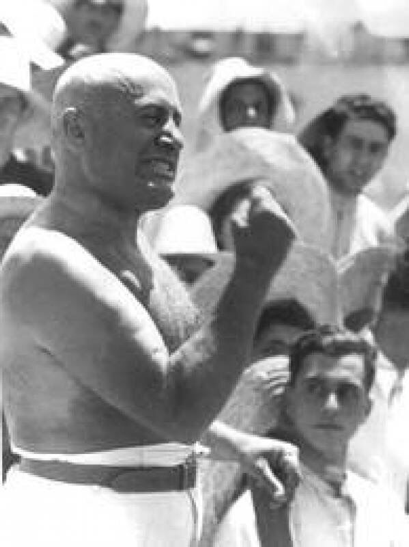

The reconstruction of the new empire required a new man. Mussolini needed a country of soldiers, that’s why virility became a defining characteristic of the ideal Italian. The new model was masculine, courageous and strong. Furthermore, he was virile, patriotic and devoted to the regime. Images produced by propaganda (Pic7), especially posters and statues, focused on the beauty of sturdy Fascist men, depicted as “eternally young and powerful”, and presented as a model the Roman soldier, recalling the idea of heritage from the Roman empire. Nevertheless, the leading model was Mussolini himself. He was the heir of the glorious Romans and the embodiment of masculinity to which everyone must strive for. Propaganda promoted the Duce’s virility and athleticism and depicted him as the ultimate sportsman, knight and warrior (pic8), personifying the ideal uomo nuovo.

Starting from the definition of people’s gender inside society through biologically determined roles, Fascism managed to create a certain social hierarchy in which women were slaves. ‘La donna deve obbedire. […] Nel nostro stato essa non deve contare’.[19] The Duce’s words and the campaigns, reforms and propaganda analysed in this essay demonstrate that it was a misogynistic society, in which it didn’t count the person’s life but the interests and success of the ‘community’. Actually, the community was not the people but Mussolini, and the only interest was the creation of the 3rd Rome.

Pic.1 Pic.2 Pic.3

Pic.4

Pic. 5

Pic. 5

Pic.6

Pic.7

Pic.8

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Barański, Z. and Vinall, S. (1991). Women and Italy. London: Macmillan in association with the Graduate School of European and International Studies, University of Reading.

- Bellassai, S. (2005). The masculine mystique: antimodernism and virility in fascist Italy. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 10(3), pp.314-335. [Accessed 21 Dec. 2018].

- Bosworth, R. (n.d.).The Oxford handbook of fascism.

- Casalini, M. (2016). Donne e cinema. Roma: Viella.

- De Grazia, V. (1981).The Culture of Consent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Grazia, V. (2005).How fascism ruled women. New York: ACLS History E-Book Project.

- Delle Vedove, F. (2001). [online] Available at: http://www.url.it/donnestoria/testi/tesi/donne%20fascismo.pdf [Accessed 5 Jan. 2019].

- Dittrich-Johansen, H. (2002). Le militi dell’idea. Torino: Leo S. Olschki.

- G. Gamberini, Sistematizzare la fede, Il Popolo d’Italia, 4 April 1928.

- Graziosi, M. (2000). La donna e la storia. Napoli: Liguori.

- Ludwig, E. (2001). Colloqui con Mussolini. Milano: Mondadori.

- Marazio Schiera, Z. (2005). Il mio fascismo. Baiso (RE): Verdechiaro.

- Marocco, G. (2016). Storia/1. Mussolini e l’emancipazione femminile durante il fascismo | Barbadillo.it. Available at: http://www.barbadillo.it/58985-storia1-mussolini-e-lemancipazione-femminile-durante-il-fascismo/ [Accessed 22 Dec. 2018].

- Martin, S. (2005). Football and fascism. Oxford: Berg.

- Mosse, G. (1985). Nationalism and sexuality. New York: H. Fertig.

- Mussolini, B. (1927) Discorso dell’Ascensione [speech to Camera dei Deputati], 26 May.

- Pickering-Iazzi, R. (1995). Mothers of invention. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sandro Bellassai, La mascolinita’ contemporanea, Carocci, Roma 2004.

- Spackman, B. (2008). Fascist Virilities. Univ. Of Minnesota Press.

- Willson, P. (2010). Women in twentieth-century Italy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Willson, P. (2014). Peasant Women and Politics in Fascist Italy. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Willson, P. and Marangon, P. (2011). Italiane. Bari: Laterza.

[1] De Grazia, V. (1981). The Culture of Consent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Pickering-Iazzi, R. (1995). Mothers of invention. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p.76.

[3] Spackman, B. (2008). Fascist Virilities. Univ Of Minnesota Press, pp.7-8.

[4] Ibid., p.12.

[5] Willson, P. (2014). Peasant Women and Politics in Facist Italy. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, p.2.

[6] Sandro Bellassai, La mascolinita’ contemporanea, Carocci, Roma 2004, p.84.

[7] De Grazia, V. (2005). How fascism ruled women. New York: ACLS History E-Book Project, p.7.

[8] Mussolini, B. (1927) Discorso dell’Ascensione [speech to Camera dei Deputati], 26 May.

[9] G. Gamberini, ‘Sistematizzare la fede’, Il Popolo d’Italia, 4 April 1928, cited in La Rovere (2002), p.61.

[10] Pickering-Iazzi, R. (1995). Mothers of invention. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p.28.

[11] Ibid., p.101.

[12] Ibid., p.XI.

[13] Perry Willson, Women in Mussolini’s Italy, 1922–1945, ed. by R. J. B. Bosworth (Oxford University Press, 2012), p.206.

[14] Willson, P. (2014). Peasant Women and Politics in Fascist Italy. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, p.161.

[15] Dittrich-Johansen, H. (2002). Le militi dell’idea. Torino: Leo S. Olschki, p.68.

[16] Bellassai, S. (2005). The masculine mystique: antimodernism and virility in fascist Italy. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 10(3), p.314.

[17] Archivio Storico Luce. (2019). Archivio Storico Luce. [online] Available at: https://www.archivioluce.com/.

[18] De Grazia, V. (2005). How fascism ruled women. New York: ACLS History E-Book Project, p.212.

[19] Ludwig, E. (2001). Colloqui con Mussolini. Milano: Mondadori.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal