Perception of Human Spaces

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Architecture |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3120 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Perception of Human Spaces

Can perception of public spaces be altered by their surrounding physical and metaphysical environments?

Introduction and Narrative

“The more broken, weather-stained, and decayed the stone and brick-work, the more the plants and creepers seemed to have fastened and rooted in between their joints, the more picturesque these gardens become.” Uvedale Price (Appleton, 1975)

Streams of light warm the back of my neck as I sit alone reading, a hushed silence screams out despite the room full of students. In my own head I am aware of no-one around me, the scraping of pencils across paper seems to echo off the walls as the people around me take notes, the discordant rhythm drawing me further into the yellowed pages. Fine characters appear crammed onto each leaf forming words, sentences, paragraphs. I don’t remember when I learnt to read. Seems almost impossible for me now to forget. At what point did these black lines begin to mean something to me?

A draught draws my attention to a cracked window, chill despite the clear skies outside. The sun catching in the corner of my eye as I turn, causing me to squint. My mind wanders to the hill on the horizon, glowing in the winter sun. A thin shadow wanders over the woodland that clings to the hillside. The wind swiftly carrying the wisps of cloud away. I can see myself there, atop that hill watching the world move around me, hearing the rustle of the long grasses, browned by the last of the summer. A dog panting as his master throws another tennis ball. The sweet taste of a cool gin and tonic from The Rising Sun lingering on my tongue, the scent of the cold clinging to my nose, my senses ablaze. My perception of that place persists even in my imagination.

Snapping back into focus I remember the book in my hands. A tale about a man who has come to recognise the smallness of his own life. Having witnessed true poverty and desperation, his perception of memories that he hated in the past, were forever changed. That which he saw as greed he grew to understand as necessity. He is now using his knowledge of the world to create a passion for bringing wildness back to our culture. However, what I want to focus on is the change in his perception, the change in how he now looks back on things in his past and sees them differently.

Altering people’s perceptions is not a new topic of discussion. A simple search on google will bring up hundreds of guides on how to change what people think of you, how to amend negative perceptions, but the level of effort required varies greatly. In some cases simple reflection will do the trick, while some others recommend a complete lifestyle change. What I want to look at is how you can change the perception of human spaces. How does an area get a bad name, and how can you guide people to see the same space in a new light? I hypothesise that a public square with the same dimensions and features would take on a different character depending on the height of surrounding buildings, the density of surrounding traffic and the cultures and histories associated with the square.

In an attempt to illustrate this hypothesis on a small scale I have created a maquette. A timber cube with six near identical faces, the difference being the natural grain on each face. All sides treated exactly the same have taken on their own characters and may be perceived differently based on their history and surroundings (refer to fig1).

Fig 1: The six faces of Four Converging Roads

In this document I will explore how both groups and individuals see and comprehend public spaces: the scientific basis for differences in cultural perception and how it leads to contrasting percepts of identical stimuli. All with the final aim to see whether these perceptions can be altered.

To accomplish this, I must set out all the factors that can affect perception. To start I will lay out the two main categories, Internal factors and External factors. The former referring to the needs of the individual driving their perception of the object. The latter encompassing all surrounding factors, external influences such as culture, history, climate, and lifestyle. I will try to delve into examples of these factors, examining them through a select few case studies.

What is perception?

In order to ask if it can be altered, first I must define perception. The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines perception initially as “the way we interact with the world through the senses” (Dember, et al., 2018) however, it goes on to talk about the different ways the topic can be discussed. The recognition and comprehension of the world around us, the environment we live in. In this sense I am, as all others are, in a state of constant perception.[AJ1]

Through my research reading into how the world is perceived by our brains, the line between science and philosophy has become blurred. The separation of science and philosophy is fairly recent, beginning with the classification of science as a separate field of study in the 19th century. Natural Philosophy, as it was called at the time, focussed on the facts of how we can see and sense the world around us. While Philosophy sought out the differences in how people comprehend that same world due to their diverse cultures, genders, influences and ages.

Physical perception through the senses involves a series of synapses that carry information to our brains capturing and processing images, sounds, smells, tastes and everything else around us (Samuel, 2012). There are many senses that are constantly relaying information within our bodies. The traditional five, which are most recognised for their roles in allowing us to perceive our surroundings.

– Vision (sight)

– Audition (hearing)

– Gustation (taste)

– Olfaction (smell)

– Somatosensation (touch)

Followed by many other types of receptors in our bodies that control anything from pain to thirst.

– Thermoception (temperature)

– Proprioception (where our limbs are in space)

– Nociception (pain)

– Equilibrioception (balance)

– Mechanoreception (vibration)

– Interoception (internal senses)

Finally leading to those which are not based on any specific sensory organ. Including time, agency, and familiarity (Metzinger, 2009).

When exploring the effect of these senses and how they work together to build a version of the world in our minds we must be informed that we are limited. There is a physical limit so the amount of stimuli we can conceive. This not only refers to that which lies beyond our field of vision, range of hearing or grasp; but all those things that we do not have the receptors to experience. The human eye has three types of photoreceptors sensitive to red, green and blue light, these light-detecting cells allow us to effectively colour in our surroundings depending on the way light refracts off each different material. In contrast many birds, reptiles and fish have a fourth receptor which deals with ultraviolet light a range on the colour spectrum that is invisible to us (Yong, 2014). Similarly, humans have between 350 and 400 types of olfactory receptors which convert the odour molecules into scents; where some animals, rats for example, can have between 500 and 1000 different receptors (Bernays & Chapman, 2017). With these facts in mind the question arises as to what the world is beyond human perception of it. Here is where the line blurs, the factual evidence stands that there is more to be seen and more to be smelt than the average person can comprehend but, whether that implies that there is more to the world, more that exists beyond the other senses, is yet to be researched, and we have yet to see whether that kind of research would be possible.

Internal Factors

In addition to the senses and their receptors there are a few internal factors that affect our perception of external stimuli. General motivations like hunger and thirst can increase an individual’s sensitivity to the relevant stimuli. Motivational factors are the most multifaceted, they prove that each individual has their own view at any one time. Someone who is feeling an immense hunger will remember thing that have satisfied their hunger in the past. When looking for a place to eat they are more open to perceiving restaurant signs and images of food (Universal Teacher Publications, 2017). In conclusion we tend to only really perceive that which is relevant to out motivations at the time, we could walk down the same high street many times and only see a certain shop when that’s the shop we are looking for. These motivations also affect our approaches toward situations, if someone is feeling insecure they may see a wide open space as a much more daunting scenario than they would on any other day, this may lead to them avoiding the situation which may in turn lead to them having a negative outlook on that open space in the future. This idea leads perfectly into learnt factors.

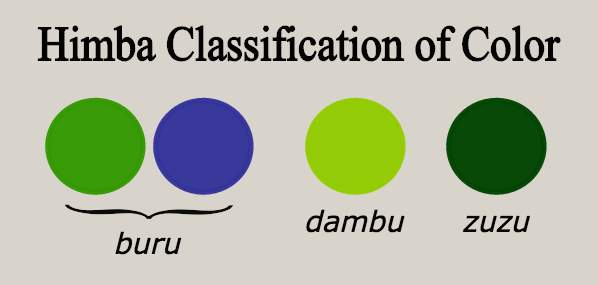

The traditional five senses can be heavily influenced by learnt factors, this is evidenced by differences between human groups in perception of distinct colours and smells. On the smallest scale an example of this effect can be found with this shape ‘9’. Those who have learnt that it denotes a value of nine will simply see it as that, the number nine. However, if they saw the exact same shape upside down ‘6’, it holds a completely different numerical value. To a culture that had never seen the shape before it would be nothing more than a line on a page; this effect is similar to how some African cultures have specific names for many shades of green that most western cultures would have difficulty distinguishing, yet have trouble when attempting to find a difference between blues and greens (refer to fig 2). These differences in learning play a heavy role in building the realities that we each live in.

Fig 2: An example of the Namibian Himbas colour classification system (Grahl, 2016)

The effects of learning are very changeable, they can mature over time, with learning to respond to new stimuli or developing new responses to old stimuli, similar but not as whimsical as motivations, learnt factors can be very difficult to change as they involve differentiating characteristics of stimuli that were neglected upon initial connection, one must re-evaluate and learn to respond to that stimuli differently (Dember, et al., 2018). Habits are an internal factor developed throughout your life and can be carried with you through many differ rent situations. They have the ability to alter the conditions under which you experience certain events. The most complex habits are unintentional, and could be sparked by the ‘wrong’ stimulus, for instance a retired soldier might throw himself to the ground when surprised with a sudden sound (Universal Teacher Publications, 2017).

External factors

The influence of external factors on our perception of external stimuli works by attempting to alter our internal reactions. Overwhelming sensory stimulation can change our motivations with varying levels of success. Colour, movement, sounds and smells of varying intensities will affect whether something sparks a physical or an emotional response from the individual experiencing them, and whether that stimulus should be received positively or negatively. External factors all work along similar lines, repetition and familiarity of a subject causes us to group things together while unique and unexpected information stands out and question what we had perceived around that topic at the time.

Perceptions of most external stimuli revolve around the Gestaltist principle of adaptation-level theory introduced by Harry Helson. The general idea is that an individual’s judgement on any given stimulus depends on their past experiences and recollections of all similar encounters in the past. The perceiver is perceptually adapted to the past sensory stimuli when attempting to perceive new information (Dember, et al., 2018).

When talking about cultural groups and group perceptions of stimuli, the most relevant external factor relates to social cues. Seeing how another individual reacts to something can have one of the strongest effects on how we react to that thing in the moment and in future situations. Learned behaviours like a fear of fire can be attributed to this idea, as many people know not to play with fire without ever having been burnt before.

Relating this idea to the hypothesis that different cultures would perceive the same public square differently depending on their own cultural background is generally understood. The question is now about the setting. The surroundings related to the space.

Relating to Urban Landscapes

Gestalt theory emphasizes that ““The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2018). In this sense it dictates that one can sense a series dots placed on a page; yet he perceives a dotted line (Dember, et al., 2018).

When translating the idea of learnt factors defining the way we perceive any external stimuli, into the urban setting of a designed landscape, we must examine examples of situations where similar landscapes have taken on different characters dependent on Internal factors.

Fig 3: Typical streets in India compared to Bristol

Figure 3 shows an example of two scenes that are in essence similar, but convey completely contrasting characters. The context of each is an urban streetscape within a city. A relatively wide paved road with shops lining each side. The density in traffic from pedestrians and vehicles is similar yet I can clearly perceive that they are clearly different places. The influence of my historical experience with typical streets around Bristol has altered my perception of the image, I have my own memory of that street or comparable streets and hence have my own conclusions as to how I perceive it. Everyone who looks at these images will see different similarities and differences and attribute different levels of importance to each.

Alcasser in Spain is a great example for demonstrating how learned historical stimuli can negatively affect perceptions of a place. A small town close to Valencia with many lovey restaurants and tourist sites, including a Visigoth necropolis and a 15th century castle, sounds lovely enough as a holiday destination. However, when you look up details of the town the first thing that comes up is the brutal kidnapping, rape and murder of three teenage girls that happened in 1992. Immediately your perception of that town is changed.

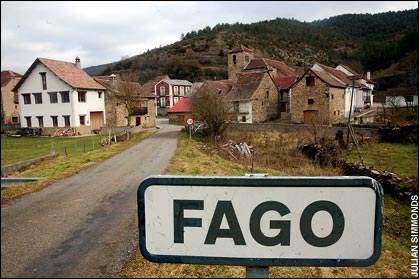

Similarly the town of Fago at the foot of the Pyrenees, a village of stone houses in a beautiful natural setting, has lost almost all tourism after it gained a very mysterious reputation. The entire village was suspected of the murder of their mayor in 2007.

Fig 4: Fago, Entire village suspected of mayor’s murder

These case studies are an extreme example but they illustrate the point, that without having experienced either of these towns you have already built a perception of them in your minds. With little evidence that what I have written is true or whether either of them even exist.

On a more relatable scale we can think about the redevelopments of areas like Gloucester Docks, which were previously underused spaces and have, since their renovation become active hubs of human activity. The physical environment was adjusted to include motivational factors in the space, these led to the growth of a new element to society.

Conclusion

In conclusion I will head back to the initial question, “Can perception of public spaces be altered by their surrounding physical and metaphysical environments?”

Looking at the theories that I mentioned I believe that not only can they be altered but public spaces are in fact defined almost entirely by their physical setting, and the history and culture that are linked to them. Depending on the perceiver whether they be an individual or a group, what they each make of the space will be different. When putting together all the factors that make up the image of an environment that the perceiver is experiencing, the reasons why we come to the deductions that we do are clearly motivated by internal and external factors.

Theodore Juriansz,

London 1997

Four Converging Roads, ca.2018

Timber & Shellac

This maquette symbolises six different places. Each face represents the same space, four converging roads creating a square. Yet each face also has its own character. The grain, the cracks, the flaws all contribute to a recognition that every side is different, while we retain the fact that they are the same.

Process

- First I cut the block into a 12×12 cube using the bandsaw.

- Then I cut grooves, 1cm in depth, into each side about 3cm from the edge

- I then sanded the cube and smoothed out the grooves

- Before finally applying three coats of shellac.

Bibliography

- Appleton, J., 1975. The Experience of Landscape. Woking: The Gresham Press.

-

Dember, W. N., Epstein, W. & Jolyon-West, L., 2018. Perception. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/perception

[Accessed 7 November 2018]. - Ingold, T., 2000. The Perception of the Environment. New York: Routledge.

-

Koerth-Baker, M., 2008. The Surprising Impact of Taste and Smell. [Online]

Available at: https://www.livescience.com/2737-surprising-impact-taste-smell.html

[Accessed 18 December 2018]. - Lapka, M. & Cudlinova, E., 2004. Perception of Landscapes: Possible Integrating Tool for Landscape Research. Ekologia, XXIII(1), pp. 170-178.

- McCarthy, R. A. & Warrington, E. K., 1990. Spatial Perception. In: R. A. McCarthy & E. K. Warrington, eds. Cognitive Neuropsycohology. Caimbridge: Academic Press, pp. 73-97.

- Metzinger, T., 2009. The Ego Tunnel. New York: Basic Books.

- Monbiot, G., 2014. Feral. London: Penguin Books.

-

Moran, L. A., 2007. A Sense of Smell: Olfactory Receptors. [Online]

Available at: https://sandwalk.blogspot.com/2007/01/sense-of-smell-olfactory-receptors.html

[Accessed 18 December 2018]. - Rogge, E., Nevens, F. & Gulinck, H., 2007. Perception of rural landscapes in Flanders: Looking beyond aeathetics. Landscape and Urban Planning, LXXXII(4), pp. 159-174.

-

Samuel, L., 2012. 7 Senses and an Introduction to Sensory Receptors. [Online]

Available at: http://www.interactive-biology.com/3629/7-senses-and-an-introduction-to-sensory-receptors/

[Accessed 19 November 2018]. -

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2018. Gestalt psychology. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/Gestalt-psychology

[Accessed 3 December 2018]. - Zube, E. H. & Pitt, D. G., 1981. Cross-cultural perceptions of scenic and heritage landscapes. Landscape Planning, VIII(1), pp. 69-87.

[AJ1]I like this

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal