Overcoming the impact of complicated grief

| ✓ Paper Type: Free Assignment | ✓ Study Level: University / Undergraduate |

| ✓ Wordcount: 2578 words | ✓ Published: 06 Jun 2019 |

Overcoming the impact of complicated grief

“Above all else, the therapist’s presence is grounded in his or her openness, receptivity and attunement to the client’s grief. Within the matrix of the therapeutic relationship, the client experiences his or her grieving self through the therapist’s responses – a potentially powerful point of connection between one suffering human being and a responsive witness. This empathic grasping of the client’s experience of loss is the most implicit and fundamental dimension of the therapeutic process.” (Kauffman, 2012).

In identifying the major causes of this distress from grief, Sogyal Rinpoche in The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying reflected that in the West most individual’s attitude was either to be in denial of death or to live in terror of it (Rinpoche, 1992). Terror of death manifests primarily as anxiety, whereas denial of the death of a loved one or other significant loss is often a core trigger of complicated grief and in many cases manifests as depression. In studying the prevalence of complicated grief, Kersting (2011) cited in (Glickman, Shear, & Wall, 2017) reported that ‘roughly’ 7%-10% of all bereaved people were affected by complicated grief.

Individuals suffering from complicated grief can be identified as individuals whose quality of living has been impacted significantly by continuous or reoccurring distress associated with the death of a loved one or other significant person. Complicated grief is severe and prolonged with impacts across important domains associated with intense yearnings, longings or emotional pain; with frequent thoughts and images of the deceased or denial of the person’s death; and a lack of a meaningful view of life without the deceased (K Shear & C Solomon, 2015).

Complicated grief refers to grief that is unfinished emotional reactions and responses to death of the individual and also the loss of the interpersonal relationship with the deceased (Erskine, 2017). Attention to what is unfinished in the grieving process is an important part of counselling and therapy for clients suffering from complicated grief as they seek or are helped to make new meaning in their life following their loss considered fundamental to overcoming complicated grief (C Park, 2008; Rowan, 2017). Failure to attend to unfinished business will result in energy remaining locked in the past and holding individuals from living fully in the present (Klingspon, Holland, Neimeyer, & Lichtenthal, 2015; O’Leary & Nieuwstraten, 2007; Rowan, 2017).

In their analysis of end-of-life practitioners’ therapeutic approaches (Currier, Holland, & Neimeyer, 2008) identified that a considerable percentage of practitioners worked to establish a strong therapeutic relationship with clients impacted by grief and one that seeks meaning making over adopting clear-cut interventions. The categories of approaches to meaning making which they identified focused on elements of process were identified by 77% of practitioners, 41% identified therapeutic presence of the helping professional and 37% identified therapeutic procedures (Currier et al., 2008). In their summary, they concluded that EOL practitioners relied on a diverse range of therapeutic activities that focused on meaning making with a convergence with important components of Shear and her colleagues’ complicated grief therapy (Shear, 2006) and with many using aspects of the Dual Process Model (Stroebe & Schut, 2010).

The research (Currier et al., 2008) is further supported by numerous meta-analyses including Common Factor research which found that the effectiveness of a wide range of psychotherapies came to similar conclusions of effectiveness in facilitating client change (B Wampold et al., 1997; Day, 2015; Erskine, 2017; Hatchett, 2017; Wampold, 2015).

This essay explores key aspects of Gestalt psychotherapy (Burnes & Cooke, 2012; Field & Horowitz, 2016; Levin, 2010; Mann, 2010; Melnick & Roos, 2007; Roos, 2013; Shaun Gallagher & Dan Zahavi; Yontef, 1993) used in counselling of individuals experiencing significant bereavement distress with emphasis on ‘unfinished’ business, which is often at the heart of complicated grief.

All counsellors working with complicated grief need to be able to incorporate elements of the various models of grief therapy, such as attachment, tasks, phases and stages, into the therapeutic process with their clients and also deal with a range of other impacts such as unresolved economic, social, health or other issues surrounding the death (Smit, 2015).

Gestalt psychotherapy is a field-theoretical approach to how we make meaning through a cycle of experiencing our needs in both psychological and physiological senses (Tonnesvang, Sommer, Hammink, & Sonne, 2010). A ‘gestalt’ represents the cycle of experience: a need becomes figural; contact is made; need is satisfied; and dissolves back into the ground. Any interruption to this cycle results in the originating need not being fully satisfied and it dissolves back into the ground unfinished. It is the interruptions within the experience of grief that are significant causes of unfinished business, such as denial; emotional distress; loss of purpose; and loneliness. A client’s inability to fully process a sensation over time results in a ‘stuck point’ or a fixed gestalt (Melnick & Roos, 2007).

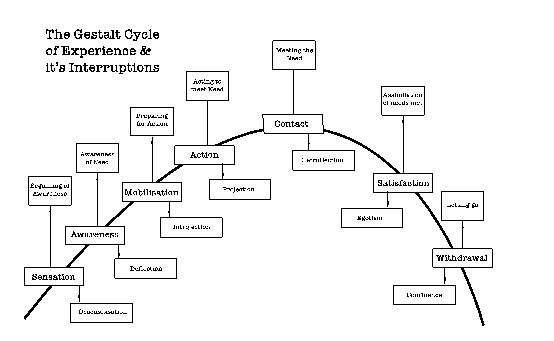

To explain the Gestalt Cycle of Experience, Table 1 provides two examples with the far right column giving an insight into how bereavement could flow through the cycle of experience (Mann, 2010). In Diagram 1, the sensation of the need arises and becomes ‘figural’, i.e. the focus or experience of an individual at that moment in time. The ‘ground’ is made up of that which is not in focus for the individual. What

Diagram 1: The Gestalt Cycle of Experience & It’s Interruptions

becomes figural comes from the ground (Bourque & Sherlock, 2016; Burnes & Cooke, 2012; Day, 2015; Mann, 2010; Yontef, 1993). Deflection, introjection, projection and retroflection are thoughts, feelings and behaviours that interrupt the satisfaction of what has becomes figural and they result in the suspension of the cycle and the creation of a state of ‘unfinished’ business (Mann, 2010; Roos, 2013).

In the following paragraphs, each of the steps in the cycle of experience will be discussed in the context of complicated grief and will examine the presenting behaviour caused by client resistance. It is important to understand that these interruptions can have positive protective functions as well as being sources of physiological and psychological stresses that give rise to complicated grief.

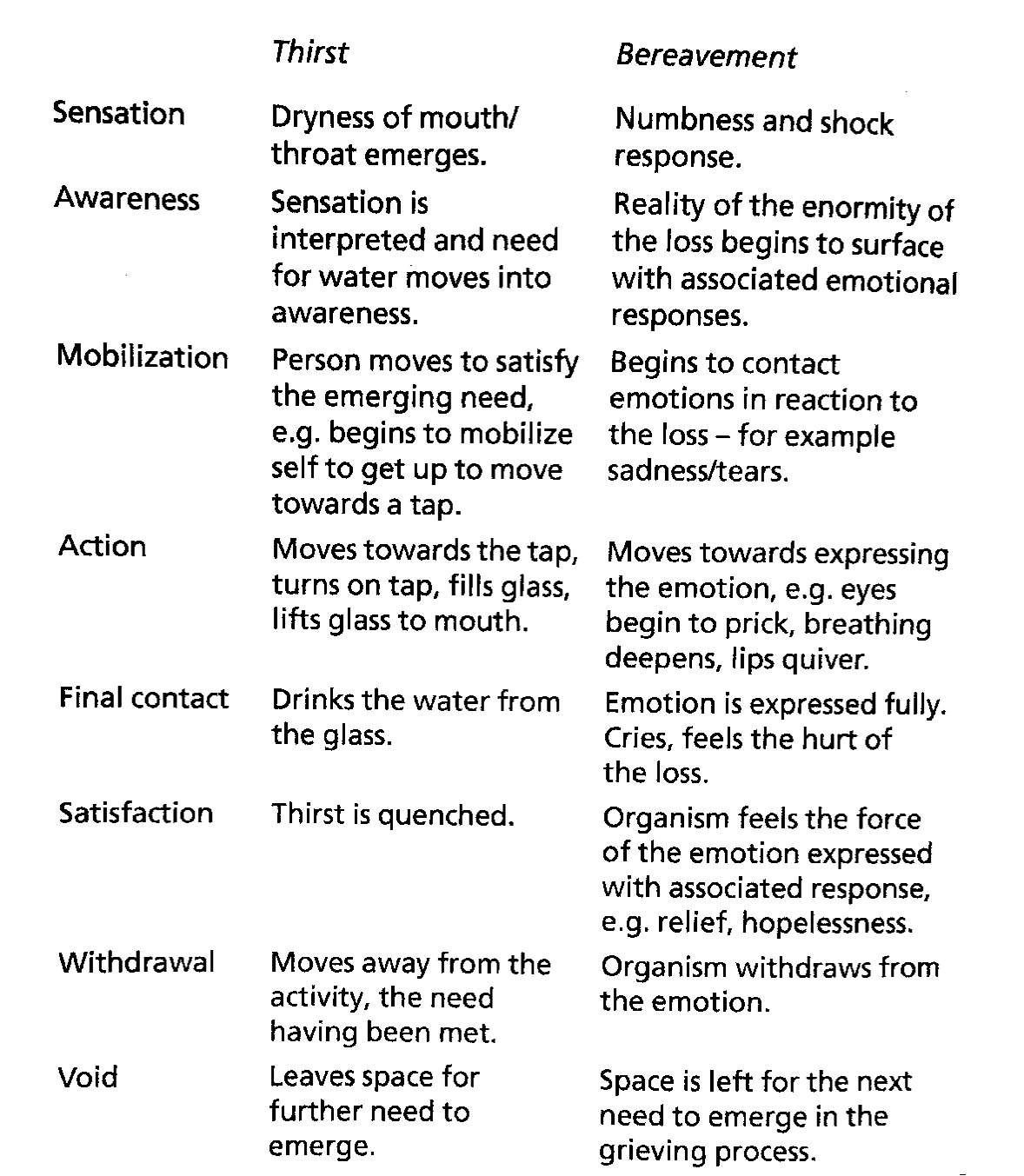

Table 1: Gestalt Cycle of Experience – conceptualising the experience of thirst and ‘uncomplicated’ bereavement (Mann, 2010).

Sensation is the very beginning of awareness of a feeling, thought or somatic response emerging from the ground of the individual. Clients who are in denial of the death often express experiencing numbness, a form of desensitisation. In another words, blocking what they do not want to recognise or experience. In this way their denial of the death results in problematic unfinished grief experience at the earliest possible time. Exploration of a client’s non-acceptance would be appropriate.

Awareness is where the sensation is interpreted and the associated reality begins todevelop. In the case of grief, the client is aware of the building of pain and emotional discomfort of the loss. However, if they choose to deflect the awareness to avoid dealing with the loss, unfinished business again arises. Deflection would be apparent in a client changing the subject or diminishing the impact with energy invested in turning away.

Mobilisation of energy is the response to the awareness of a need that is seeking satisfaction. This could be where a client begins to make contact with their emotions, for example anger or sadness. The interruption for mobilisation is introjection, most likely learned responses, traits or coping mechanisms that have resulted in internalized rules of shoulds, oughts and other absolutes. Introjections blunt the affects of awareness by prevent the display of emotions or the experiencing on the inside of something that should be experienced on the outside. In the case of the awareness of sadness, the mobilisation of the energy to cry would be prevented by introjection. The suppression of emotional responses is a significant example of unfinished business and more than likely fixed gestalts or stuck points.

Action moves towards expressing the emotion. In the case of sadness, the mobilisation of the emotion builds physically in readiness to cry and other somatic responses. Action is interrupted by projection, which tends to occur when an aspect of the person does not fit with their self-concept and it is projected onto other people including the therapist, objects or institutions. The therapist should encourage the client to own their projections and to take responsibility for what they are thinking.

Contact is where the actual response to the need occurs. In the bereavement example, the client’s emotion of sadness is expressed, tears flow and they feel the hurt at the loss. If the client prevents contact and turns the action of the awareness back on them, a form of retroflection will occur and the cycle interrupted. In retroflection the client resists contact with their environment resulting in the client experiencing on the inside what should be experienced on the outside. Retroflection can also give rise to splitting, which is where one part of the client is the ‘doer’ and the other part of the client is who it is ‘done to’. Another type of retroflection is providing for oneself what is not available externally, for example self-soothing, which can be a healthy substitute for what is missing. However, if the substitution becomes habitual and what is missing is not actually satisfied, then a stuck point or fixed gestalt can become established. Depression, resentments, self-destructive acts, submissiveness, or getting sick all the time are good examples of clients exhibiting retroflections.

Satisfaction is when the original need has been met. However, the egotism of the individual may mean that they never feel completely satisfied and that again results in unfinished business. It is apparent in clients who step outside of themselves and becoming a spectator or commentator on themselves. Egotism interferes with the feeling of being fully satisfied and gives a deceptive sense of self.

Withdrawal the need is fully satisfied and the individual withdraws from the experience and the cycle ends waiting for the next sensation to arise. Confluence is the last interrupt and occurs between satisfaction and withdrawal. It is present when a client does not know how or does not wish to let go of the need preventing the cycle from completing. In the case of bereavement, it would be where a client cannot let go of their sadness possibly because they have nothing to replace it with. Therefore, they remain stuck and if this becomes chronic it is more than unfinished business it is a fixed.

Utilising the cycle of experience in complicated grief therapy and counselling is very much one of oscillation in which cognitive, emotional and behavioural needs are allowed to arise from the client’s ground to become figural with the aim of being worked through to completion and satisfaction or interrupted resulting in unfinished business to be addressed at a time that the client is ready. The Dual Process Model (DPM) also focuses on a regulatory process labelled ‘oscillation’ between two categories of stressors associated with complicated grief, those that are either loss-orientation or restoration orientation (Stroebe & Schut, 2010).

One of the key therapeutic interventions in working with unfinished business is chair work.

If we consider the start of the first session for a moment, the counsellor who may have extensive experience in working with loss and grief may only have what the client brings to the here-and-now of the session to work with (Yalom, 2002). If the client is experiencing complicated grief The combination of the identification the resistances that give rise to the client’s unfinished business informed by the stressors categories of the DPM provide a strong and evolving case conceptualisation from which to engage the client in overcoming the overwhelming feelings of loss and detachment (R Neimeyer & Currier, 2009). In focusing on what is top of mind for the client, not only does the counsellor gain some awareness of the nature of the client’s distress, so too does the client.

Conclusion

In society, we see how most individuals are disappointed every day when their beliefs in the permanence of people, things and organisations are shown to be wrong. Yet, the same individuals only struggle with the impermanence of life when confronted by dying and death.

In Buddhism (Geshe Lhundub Sopa, 2004), impermanence is the first aspect of the first noble truth, which is that life is full of suffering and all phenomena are impermanent.

References

B Wampold, G Mondin, M Moody, F Stich, K Benson, & Ahn, H. (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies- Empiricially, “all must have prizes.”. Psychological Bulletin, 122(3), 203-215.

Bourque, N., & Sherlock, E. (2016). Integrating Gestalt psychotherapy into social work practice with adult oncology patients. Social Work in Mental Health, 1-16. doi:10.1080/15332985.2016.1191583

Burnes, B., & Cooke, B. (2012). Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory: A Review and Re-evaluation. International Journal of Management Reviews, n/a-n/a. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00348.x

C Park. (2008). TESTING THE MEANING MAKING MODEL OF COPING WITH LOSS. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(9), 970-994.

Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2008). Making sense of loss: a content analysis of end-of-life practitioners’ therapeutic approaches. Omega (Westport), 57(2), 121-141. doi:10.2190/OM.57.2.a

Day, E. (2015). Field Attunement for a Strong Therapeutic Alliance. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 56(1), 77-94. doi:10.1177/0022167815569534

Erskine, R. G. (2017). What Do You Say Before You Say Good-Bye? The Psychotherapy of Grief. Transactional Analysis Journal, 44(4), 279-290. doi:10.1177/0362153714556622

Field, N. P., & Horowitz, M. J. (2016). Applying an Empty-Chair Monologue Paradigm to Examine Unresolved Grief. Psychiatry, 61(4), 279-287. doi:10.1080/00332747.1998.11024840

Geshe Lhundub Sopa. (2004). Steps on the Path to Enlightenment (Vol. 1: The Foundation Practices). Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Glickman, K., Shear, M. K., & Wall, M. M. (2017). Mediators of Outcome in Complicated Grief Treatment. J Clin Psychol, 73(7), 817-828. doi:10.1002/jclp.22384

Hatchett, G. (2017). Monitoring the Counseling Relationship and Client Progress as Alternatives to Prescriptive Empirically Supported Therapies. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 39(2), 104-115.

K Shear, & C Solomon. (2015). Complicated Grief. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(2), 153-160. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1315618

Kauffman, J. (2012). The Empathetic Spirit in Grieg Therapy. (I. R. Neimeyer Ed. Vol. Techniques of group therapy: Creative practices for conseling the bereaved). New York: Routledge.

Klingspon, K. L., Holland, J. M., Neimeyer, R. A., & Lichtenthal, W. G. (2015). Unfinished Business in Bereavement. Death Stud, 39(7), 387-398. doi:10.1080/07481187.2015.1029143

Levin, J. (2010). Gestalt Therapy- Now and for Tomorrow. Gestalt Review, 14(2), 147-170.

Mann, D. (2010). Gestalt Therapy. East Sussex, U.K.: Routledge.

Melnick, J., & Roos, S. (2007). The Myth of Closure. Gestalt Review, 11(2), 90-107.

O’Leary, E., & Nieuwstraten, I. M. (2007). Unfinished business in gestalt reminiscence therapy: A discourse analytic study. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 12(4), 395-411. doi:10.1080/09515079908254108

R Neimeyer, & Currier, J. (2009). Grief Therapy- Evidence of Efficacy and Emerging Directions. Current Directions in Psychological Science,, 18(6), 352-356.

Rinpoche, S. (1992). The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. San Francisco: Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.

Roos, S. (2013). Chronic Sorrow and Ambiguous Loss- Gestalt Methods for Coping with Grief. Gestalt Review, 17(3), 229-239.

Rowan, J. (2017). Existentialism and the dialogical self. Existential Analysis, 28(1), 82-92.

Shaun Gallagher, & Dan Zahavi. (24 Dec 2014). Phenomenological Approaches to Self-Consciousness. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/self-consciousness-phenomenological/

Shear, M. (2006). The Treatment of Complicated Grief. Grief Matters: The Australian Journal of Grief and Bereavement, 9(2), 39-42.

Smit, C. (2015). Theories and Models of Grief- Applications to Professional Practice. Whitireia Nursing and Helth Journal, 22(2015), 33-37.

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: a decade on. Omega (Westport), 61(4), 273-289. doi:10.2190/OM.61.4.b

Tonnesvang, J., Sommer, U., Hammink, J., & Sonne, M. (2010). Gestalt therapy and cognitive therapy–contrasts or complementarities? Psychotherapy (Chic), 47(4), 586-602. doi:10.1037/a0021185

Wampold, B. (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 270-277.

Yalom, I. (2002). The gift of therapy. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Yontef, G. (1993). Gestalt Therapy: An Introduction. In Awareness, dialogue & process – essays on gestalt therapy. Highland, N.Y.: Gestalt Journal Press.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this assignment and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal